CNC: Accuracy, tolerance and fit, oh my.

- Jan 2, 2020

- 3 min read

Something that has been nagging at me for decades as a casual woodworker is how to get better fitting joints. My recent step into using a CNC router has only increased the nagging sensation. With my little CBeam machine I can make parts with about 2/1000 of an inch accuracy. And my machine is pretty tight so I can consistently make parts of a given size. Yet, if I make a 1" hole and cut a 1" plug, even though they are both exactly 1", the plug will not fit in the hole.

But, I'm sure the experienced machinist, woodworker or just generally thoughtful person will say "Duh, the plug needs to be a bit smaller". And they, of course, are right. Though a machinist might mumble something about an arbor press for force fit and toss out modulus of elasticity and other terms.

We all know that loose joints are bad and, as a woodworker, one of my goals has always been to have nice tight joints. A mechanically tight fit means that glue (or, shudder, fasteners) don't have to work as hard to keep the piece together. Though, if the fit is too tight, other problems arise. You can starve the joint of glue or the glue will expand the joint faces enough to make it hard or even impossible to fit them together. And in the worst case, forcing the fit can split or otherwise damage the joint. And when building for the long term a forced fit joint can crack with seasonal movement. Yes, there is such a thing as "too tight joints". So, what makes for a "good fit"?

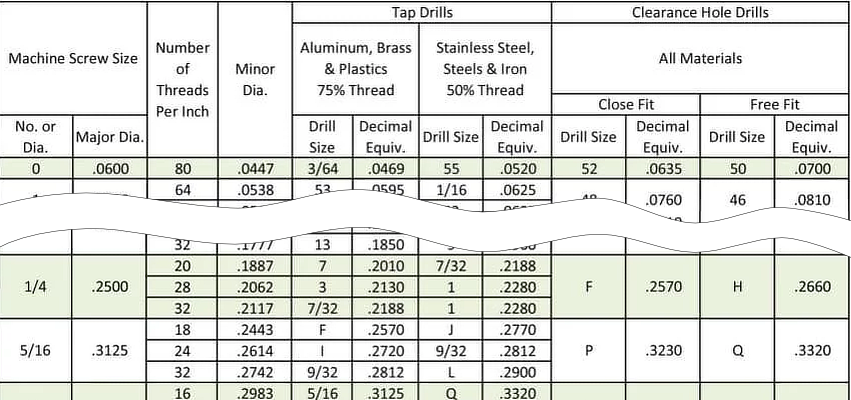

Looking at a bolt hole chart can be instructive. If you look at the 1/4" line in the above chart, you will see two columns - Close Fit and Free Fit. You can see that the Close Fit hole is 7/1000" larger and the Free Fit is 16/1000". In woodworker terms, the Free Fit size is basically 1/64". This is for metal which cuts very cleanly. In wood, the fibers and generally rougher surface will require more room. But in either case, the concept is clear - you need some allowance for even a truly tight fit.

So, back to that 1" plug and 1" hole. How much room does a good joint need to have? For woodworkers with lots of experience, the answer is "I'll know it when I see it". It's common practice to "sneak up on a fit" by, for example, cutting a tenon slightly larger and sanding or chiseling it down to tune the fit. Understanding how glue will cause the aforementioned tenon to swell is very much a part of that calculus. But, different materials can call for different fits. Pine vs MDF vs Baltic Birch Plywood vs Maple - each is different. And there really is no substitute for hands on experience. By the way, for hand cut joints, I still use the "sneak up" approach.

With a CNC router, you can make very precise cuts. So, I have been building in some allowances that get me excellent joints. With BB Plywood and MDF, an allowance of .01" ( 10 mils or 0.25 mm) gives nice tight and glueable joints.

Two additional points - cutter size and runout. You should get in the habit of measuring your router bit for it's exact size. Bits can vary a surprising amount, especially Chinese ones. I have a nominal 1/8" bit that measures 0.117" (should be 0.125") and have heard reports of bits as small as 0.110". I use the measured bit size in my CAM software. Also, your bit and collet can combine to add runout which makes for a larger effective size of bit. If you have a dial indicator, you can get a sense of run out. Measuring your kerf, while not as precise, can help you get a handle on that. Even high quality spindles and routers can have as much as 2 mil of runout. And cheap ones WILL be worse than that. Also, the effective increase in the kerf width will be twice the runout. These runout and bit size numbers may not seem like a lot but can make the difference between a good fitting joint and a bad one.

Comments